| Top |

1 The Lacquer Process

-----The Lacquer Tree

-----Qualities of Lacquer

-----Base Materials: Wood, Bamboo, and metal

-----Preparing the Surface

-----Colorants

-----Gold-leaf

-----Use of Local Materials

2-Techniques of Lacquer Decoration

-----Traditional Incising Techniques

-----Applying Colors

-----Finishing

-----Innovations in Incised Lacquer

-----Black Etched Wares

-----Green Wares

-----White Wares

-----New Colors and Quicker Processing

-----Painted and Layered Lacquerware

-----Marbled Lacquer Japan Yun

-----Gold leaf Lacquerware Shwei-zawa

-----The Gold leafing Process

-----Blue and Blod Wares

-----Incised Gold Wares

-----Combination Wares

-----Relief-moulded Lacquer Thayo

-----Technique of Relief-moulded lacquer

-----Hman-zi Shwei-cha

-----Technique

-----'Disco Gold-leaf'

-----Man-hpaya

-----Technique

3- Lacquer ware Objects for Secular and religious Use

4-Lacquerware for Religious and Ceremonial Use Votive Food Receptacles

| The Lacquer Process |

The Lacquer Tree

The lacquer used in Burma is called thit-si (wood resin), which is the sap of the Melanorrhoea usitata, a tree native to Southeast Asia. It differs slightly from the Chinese and Japanese species Rhus vernicifera and is completely unrelated to the shellac used in India and Europe, which is made from the resinous secretion of the insect Coccus lacca.

The lacquer tree grows wild up to elevations of 1,050 m on laterite and sandy soils in the drier forests of Burma. Reaching 15-18 m in height with a girth of 2-3 m when fully grown, its first branches begin several meters above the ground (Rodger 1936:63). Covered with a canopy of large leaves, it is a fine upstanding de3nizen of the rain forest and is particularly striking in full bloom when it assumes a mantle of thick creamy white blossoms witch later turn red. The flower buds emit a fragrance reminiscent of apple blossoms. Being edible, the buds are sometimes used to flavor a curry. To some Burmese, falling lacquer blossoms are the harbinger of a storm.

The wood of the lacquer tree is a rich dark red flecked with yellowish streaks. It acquires a deeper tone with age. This dense hard durable wood takes on a high polish and is suitable for high quality furniture. Because it is close-grained, it has been a popular wood for house posts, bridges, anchors, and handles for tools and weapons. It was once widely used for making charcoal (Shway Yoe [1882] 1963:275). Despite its varied uses, there seems to have been no attempt to cultivate it using plantation management techniques.

The resin is tapped by making two diagonal notches 20-5 cm-long to form V-shaped incisions 5 cm deep in the trunk of the tree. A grey viscous liquid exuding from the notch slowly trickles into a small bamboo cup which is secured by inserting a sharpened edge into the base of the V. Up to four or five incisions may be made, one above the other, to a height of nearly 2 m on a full grown tree. Once a tree has been tapped, this area has to be left for four to five years to heal completely before being tapped again. If a tree is large enough, it is possible to rotate the tapping and t hereby produces lacquer continuously. Tapping, unless excessive, does not seem to have an adverse effect on the life of a full-grown tree (Morris 1919: 2 and Hla Aung 1959:188).

Although in theory a tree can be tapped all year round, this activity is usually avoided during the fruiting season from January to march. The lacquer tends to be thin at this time and does not take on such a brilliant polish (Shway Yoe [1882] 1963:275). The resin is collected in dry weather, because the presence of rain either washes away or dilutes the lacquer may be preserved either by storing in airtight containers or by pouring approximately 5 cm of water over the surface. The water seal prevents air from reaching the lacquer and causing solidification. However, the addition of water do3s not improve the quality, for the lacquer soon absorbs some of the moisture which alters the color and renders it less durable and glossy.

Qualities of LacquerThe best quality of lacquer is called this-si ayaung-tin, a deep lustrous black lacquer. This is resin, which has just been tapped from the tree. It gives the best gloss, as the water content is less than 25 per cent. Second quality or 'brown' lacquer contains up to 30-35 per cent water while inferior or 'yellow' lacquer may have up to 40-45 per cent water.

Raw lacquer, an oleo-resin, consists of catechol and urushilo compounds along with water, various gummy substances, and proteinaceous matter making up to balance. Hardening to a jet-black color takes place when the urushiol materials polymerize on the diastolic matter. To dry successfully lacquer requires a warm temperature between 20-8 degrees centigrade and a relatively high humidity, preferably over 55 percent (Garner 1979:22 and Strahan and Maines 1999). At that time lacquer must also be kept away from direct sunlight which tends to pucker and blister the surface, although fairly warm conditions are required, temperatures above 45 degrees centigrade are too high and will interfere with the setting process. The end of the Burmese rainy season (around September) is considered to be the ideal time for drying. At this time climatic conditions are moist but not too hot (Khin Maung Gyi 1963: 16-21).

Most workshops construct an underground cellar (taik) on the premises for drying lacquer. This cellar is bout 2.5 m high and averages about 3-sq. m in area. Step lead down to an earthen floor surrounded by brick or concrete walls lined with mat-covered wooden shelves. An earthen floor is essential for generating a moist atmosphere. A heavy trapdoor assists in maintaining moist, dark conditions. An average sized cellar can hold between two and three hundred pieces of drying lacquer at one time.

The best raw lacquer comes from Mokeil, Loilem, Keng-tung, and Law-sawk in the Southern Shan States. Katha in the Sagaing district and Bha-mo in Kachin State also produce high-grade lacquer. Second quality lacquer comes from Hsen-wi in the Northern Shan States, and from Pyinmana and Lewe north of Taung-ngu. Lacquer is usually purchased in ten viss cans. Early 1980 prices ranged from 500 to 700 kyat per can depend on quality.

Prior to use, the lacquer resin is usually warmed in the sun for a short time. While warming it turns from a light greyish-brown color to a glossy black. Lacquer is somewhat caustic and has been known to cause inflammation to the skin (Garner 1979: 21). Prolonged exposure can damage the lungs, while extended contact with the substance within the confines of the cellar can also irritate the eyes.

Base Materials: Wood, Bamboo, and metal

Lacquer in many eastern civilizations initially served as a waterproofing varnish and has been used to caulk boats in China, Vietnam, Thailand, and Burma. An excellent adhesive, it has also been used to varnish stone, iron, and leather, as well a s to waterproof, stiffen and preserve woven baskets, paper, and cloth products. A number of ethnic groups in Southeast Asia, particularly in the upland areas continue to use lacquer for such purposes. For example, the Karen people of Burma continue to reinforce their distinctive collecting baskets and woven betel boxes with one of two coasts of lacquer.

Over the last two millennia, however, these early practical uses have largely been obscured by lacquer's unique potential for beautifying objects to which it has been applied. For decorative lacqerware the process begins, in most cases, with the construction of a base object in either wood or bamboo. Softwoods such as baing (Tetrameles nudiflora), di-du (Bombax insigne), and let-pan (Bombax malabaricum) are used to produce everyday objects such as rectangular boxes, folding tables and screens. Where greater weight and durability are required for structural objects such as monastic furniture and architectural fixtures, teak wood (Tectona grandis) is used. Many gilded and inlaid objects are made from wood.

The best quality lacquer is usually made from a base of Bamboo. Tin-wa (Cephalostachyum percale) or myinwa (Dendrocalumus strictus) from the central Sagaing Division are considered the best with their 15 m by 8-cm clumps and widely spaced interposed (Khin Maung Gyi 1981: 3 and Rodger 1936: 77-8). After frying, the bamboo trunk, which is retailed in 3 m-long clumps in handles of one hundred, is cut just below the joints with a machete. These cylindrical pieces are then split with a sharp knife into long thin strips, which may be flat, or round depending on the type of receptacle to be made. The strips can be coiled, twisted, or woven into the desired shape and dimension. The outer bark and inner core sections of the bamboo are not used.

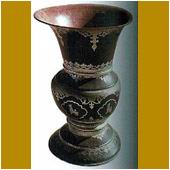

In the case of coiling, the bamboo is split into 1-2 cm-wide strips by women who then pass them on to the men for the next step of the process. The first coil is held firm by interlocking notches reinforced with a knot made from cotton thread. Subsequent strips of bamboo are added, one after the other, to achieve the desired shape. Throughout the process the artisan checks the object for size and taps it now and then to make sure that the bamboo coils fit together tightly and evenly. Trimming and shaving the object with a sharp knife is also part of the process. Some objects such as flower vases are made in two or three parts which are alter fitted together to create a continuos form.

For items requiring a rounded surface, bamboo strips are twisted and woven together by women. As with basketry, several weaves are possible. A three-fiber twisted weave is very popular with many establishments. For the finest wares requiring a extremely light pliant framework, a warp of ultra-fine bamboo is interlaced with a weft of hair from a horse's tail. This woven combination produces a bowl so flexible that the opposite sides may be pressed almost tougher without damage to the lacquered surface.

In the case of bowls the base is first woven on a circular flat surface resembling a stool. The center is then pierced and placed over a spindle, which rests on supports. A wooden mould or chuck of the desired size and shape is fastened to the spindle and the walls of the bowls are pulled up and woven around it. In the case of betel boxes the base and sides are woven separately and joined later. The large flat surfaces of objects such as small tables, baskets, and food containers may be cut from previously woven matting. The matting is then attached to a wooden or bamboo framework to create the desired form. On many objects more than one technique is evident. A number of larger bamboo food receptacles may comprise a woven bowl covered by a coiled lid.

Many simple objects such as rectangular boxes and small tables are sawn and assembled from planks of wood by carpenters. Some of the most beautiful of the circular lacquer receptacles have been artfully fashioned into very distinctive shapes by Burma's imaginative and talented wood turners, who with simple foot-operated lathes, are able to convert a simple block of wood into a curvaceous vase, a flaring rice receptacle, or a monumental stand supported on a pedestal of bulbous rungs. Wood carvers have also lent their skills to beautifying lacquer objects and screens with fine openwork embellishment and to the decoration of finials and appendages with artful zoomorphic forms.

Sheet metal is also used as a foundation base for Burmese lacquer ware. The majority of monks' bowls used in Burma today is made from beaten metal covered with lacquer. Even bowls made of earthenware are finished with a coat of lacquer. The hti, the fanciful gilded umbrella that crowns the apex of virtually every pagoda in Burma, is made from concentric circles of iron connected by lacquer and gilded openwork shapes cut from sheet metal. Metal frills of gilded openwork may be added for further decoration to some wooden lacquer object.

Preparing the Surface

Once the base object is made, it surface must be prepared for lacquer ornamentation. The object is first sealed with a layer of lacquer which ash been mixed to a smooth paste with finely sifted ground clay. This coating fills the larger interstices. The object is then put in the cellar to dry for three to ten days depending upon in the weather. After hardening, the object is smoothed and polished with wet pumice stone on a hand-operated lathe, which consists of a spindle resting on two supports. A leather string attached to the spindle is tied around a stick resembling a violin bow. The operator sets the lathe in motion by pushing the bow diagonally to and for over the spindle to wind and unwind the leather cord around it which causes the spindle to rotate.

Once the object has been polished, a second coating of finer material (htaung-thayo) is applied, it is made by mixing lacquer with finely sifted ash made by burning teak sawdust. Glue from boiled rice may sometimes be added to increase adhesives. For the finest work, the ash is obtained from burnt cow dung, rice straw, or powered bone which has been carefully sifted through a cloth before being blended into the lacquer to form htei-thayo. The remainder of the process is one of continual smoothing and coating with lacquer, alternating with drying in the cellar until the entire rough part shave disappeared. As the article comes closer to completion, the something is more carefully done with a variety of abrasives such as the leaf of the dahat tree (Tectona hamiltoniana), rice (padi) husks and water, fossilized wood or teak charcoal.

The entire process, including drying periods, can take as long as six months. For everyday plain wares the process is completed with a final coat of good quality lacquer. The artisan is left with a smooth shiny black lacquer object, which is rubbed with sesame oil and polished to a high brilliance with a chamois of buffalo leather.

Colorants

For colors other than black, the natural color of lacquer a variety of pigments are used. The characteristic vermilion of Burmese lacquer, called hin-thabadca, comes from finely ground cinnabar (mercuric sulhpide) which is imported from China. Before being applied to as surface, the colorant is mixed with a little lacquer resin and worked to a smooth consistency with some tung oil (shan-zi) which comes from the tree fruit of the Aleurites triloba or dipterocarpus turbinatus. Minute quantities of' special' additives might also be included. It was said that the formula for hin-thabada was traditionally ' a so closely guarded secret that a husband [would] not impart it to his wife and a father only to the most trusted of his son's (Hardiman 1912; 125).

On inferior wares a cheaper alternative-red ocher from India (mye-ni), is used (Berney 1832: 171). The color is less brilliant and after extended use may exhibit a tendency to flake. Red is the most popular color for finishing the interior of receptacles.

In recent years, a deep chocolate brown has become a popular color on both the exteriors and interiors of Burmese lacquer. Adding a higher proportion of thit-si to the hin-thabada pigment generally makes it. On inferior examples the brown is dull and thick. On better quality wares an effort has been made to increase the sheen by the addition of thinner better quality lacquer in more layers. According to Pagan lacquer entrepreneur U khin Maung Maung, early Burmese examples of brown lacquer were noted for their sleek shiny interiors. Unfortunately, the art of making such a colorant (bok yaung) appears to be lost to posterity. Individual artisans to rediscover the art of making lustrous brown lacquer are conducting experiments.

Yellow (sei-dan) is made from orpiment (arsenic trisulphide) which is found in the Shan States. It is pounded and washed several times until a fine impalpable powder remains. This is mixed with a pellucid gum such as damar. When ready for use, it may be applied dry or be worked up with a small amount of thit-si resin and shan-zi oil to attain a suitable consistency. To make orange, orpiment is added to the hin-thabada.

A blue color (me-ne) was originally made from finely ground indigo which like the textile dye, traditionally came from the plant Indigofera anil. Present day indigo comes mainly from Germany and India. Blue pigment, however, was rarely used in traditional Burmese lacquer work, for the indigo does not combine well with the catechol substances of raw lacquer, resulting in rather a dull finish. One part indigo was added to ten parts of orpiment to produce a traditional green color (Spearman 1880: 419). With age, many such green lacquerwares have come to assume a leasing opaque turquoise hue. Because the process of producing green is rather time consuming, coupled with the fact that indigo pigment is in short supply in Burma, many craftsmen now substitute green enamel paint for the original indigo and orpiment.

Gold-leaf

Gilding by applying gold leaf is a process synonymous with Burmese lacquerware and Burmese art in general. The act of gilding in the Buddhist world is considered a meritorious deed and many objects intended for religious and royal use are embellished with gilt decoration. In Chinese and Japanese work, gilding with powdered paint is generally preferred. In Burma, however, most objects are gilded with small tissue-thin squares of golf-leaf (shwei-bya) made from 24 carat gold panned in the rivers of northern Burma. Powdered gold paint is mostly confined to objects of inferior quality.

It is possible to see gold leaf being made by time honored methods in the Myet-jpayat quarter of southeast mandalay (near 36th and 77-78th streets). Gold leaf begins as a thin stick of gold about 1 cm wide, 0.5 cm thick, and 15 cm long. It is first heated and drawn out in a small machine with rollers until it is about 11.5 cm wide. It is then stretched by hand and beaten until it is approximately 30-cm ling by 60 cm wide. This fine sheet of gold foil is cut into 1-cm2 pieces, each of which is placed, on a 8 cm piece of bamboo paper lightly powdered with rice flour. Some four hundred of these, interleaved at regular intervals with rice straw paper, are piled one upon the other before being wrapped in tow layers of deerskin.

This package is given to a beater who secures it to a wooden frame clamped to a stone surface. He then strikes the package evenly and rhythmically with a 1.5-3 kg weight hammer for half an hour. This initial hammering causes each gold fragment to spread out over six times the original area. After the first beating, each fragile sheet of gold is cut into six pieces with bamboo or bone knives by women workers who labor in a windowless room to minimize dust contamination and the action of air currents in disturbing the fragile sheets of gold leaf. Once again, each piece is placed on a sheet of lightly powdered bamboo paper. This time the papers are stacked into a bundle of about 1,200 sheets. This bundle is protected by the addition of ten sheets of rice straw paper before being rewarded in deerskin. The packet is hammered alternately by two men for about two hours before the contents are inspected. On reaching the optimum size, the gold leaf is re-cut into pieces and packed into sets of nine hundred sheets and rewarded for a final beating which lasts about three hours. On completion of the beating process, women trim the gold leaf to the required size. Each small sheet is interleaved with rice straw paper, before being packaged in small bundles for sale (The Myat: 1959: 152-7 and Searle 1928: 146).

Use of Local MaterialsWith the exception of one or tow pigments, virtually everything required for lacquer production is produced in Burma. The bamboo and wood for the receptacles, the raw lacquer itself, and various oils and additives all come from the forests of Burma. The use of other local products such as teak sawdust, bone ash, rice husks, ochre, and fossilized wood further reflect the Burmese lacquer worker's ability to use local materials creatively. The tools and the machinery used in producing lacquerware are simple but effective. Knives, stili, pounders, and lathes have all been cleverly adapted to perform the tasks associated with making lacquerware.

Producing lacquerware is time consuming, but it can be effectively organized as a cottage industry. An entire village may be involved in the various phases of lacquer production. One part of a village might make receptacles, while another locality produces the matting required. Other areas might be responsible for decorating and finishing. In some villages, many families have been involved in the lacquer industry for many generations. Children begin learning the craft at an early age. They start by helping their parents and elder siblings at tasks of progressive difficulty. By the time they reach adolescence, the majority of them are proficient craftsmen. In a family business there may be a division of labor where the women make the receptacles while the men decorate them. Older people are often involved in the finishing process here superior strength and 20/20 visions are not essential. Women usually handle the financial side of the business.

| Techniques of Lacquer Decoration |

Incised lacquerware Yunburma is fam8ous for a unique style of incised lacquerware decoration called yun, which is also, the generic Burmese term for lacquer. The surface of an object is engraved through tow to three priming layers with a fine iron stylus (kauk) and the incisions are them filled with coloring matter according to the dictates of a design. This technique evolved in chian during the Warring States period (475-221) BC) and continued to be practiced during the Han period (206 AC-AD 220) and then appears to have declined in popularity in favor of other decorative lacquer techniques. However, there was a revival of int4erest in China during the Yuan dynasty (AD 1280-1368) which was noted for its linear gold etched (chiang-chin) lacquer designs (Garner 1979: 16-17, 40, 156-7).

As previously noted in the introduction, this decorative lacquer technique was probably first seen in Burma on tribute items from neighboring states. There is mention in the Kalyani Inscriptions of 1476, of 'twenty-two variegated 'Haribhunja" [Haripunchai, Thailand], betel boxes with covers' that were formally presented as gifts to visiting monks from Sri Lanka by King Dhamma-Zeidi of Pegu (r. 1460-92) (Taw Sein Ko 1893: 41). The King of Chiang Mai is also reported to have sent lacquerware to Pegu as an item of tribute to the victorious King Baying-naung in 1557. Some seven years later as a punishment following an unsuccessful rebellion against his overlord, the King of Chiang Mai was forced to send numerous craftsmen, including lacquer workers, to Baying-naung's court at Pegu.

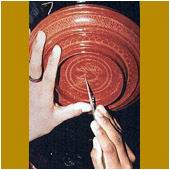

Traditional Incising TechniquesThe decorative process for yun wares begins with the incising of a freehand outline of the design into the smooth glossy red, black or brown surface of the object. No stencils or patterns are used. The lines vary greatly in density and complexity depending on the design. A rhythmic liveliness and freedom of movement characterize the best-incised lacquerware patterns with figural elements subtly blending into the decorative details of the groundwork. Lacquer patterns resemble line drawings rather than formal engravings. Simple parallel lines, a feature of yun border decorations, are usually incised with a comb of three or four sewing needles firmly fixed through a bamboo rod. For circular sets of parallel lines, needles inserted into a modified compass are used. A skilled craftsman is able to space the design so accurately that on completion it is virtually impossible to see where the design began and ended (Hla Aung 1959: 190). On the finest work at Pagan, young men are responsible for the first set of incisions, which block out the main complainants of a design. Subsequent incisions require the finely tuned eye-hand coordination of highly skilled young women to attain the intricacy of pattern characteristic of the finest wares.

Once the primary incisions have been mad, the red hin-thabada colorant is smeared over the object three to four times to make sure that all incisions are filled with the coloring matter. The article is then left to dry for three to four days in the cellar. When 'set' the excess pigment is removed by polishing the object on a lathe with wet rice husks. For the best results each color is applied twice and the process repeated. After polishing, the article is returned to the cellar to dry completely. Once dry, a glue made from the resin of either the neem (Azadirachta indica) or the acacia tree (Acaia farensiana) is painted over the newly incised part of the object to seal the read color within the engraved lines.

Once the glue has set, a series of new engravings are made for the next color, which is usually green. As with red, the green coloring matter is rubbed over the entire design and left to dry for a few days. The superfluous coloring matter is then removed from the etched surface in to same manner as before, leaving behind red and green in separately incised lines. Green appears only in the new engravings. The final colors, yellow and orange, are applied in the same manner. The entire design is then completely sealed with a final coat of lacquer resin mixed with a little tung oil.

FinishingOnce the object is completely dry, it is carefully polished with wet rice husks, ground fossil wood, and/or teak charcoal. This gives a fine luster to the red or blank lacquer ground which shines through the main engraved designs highlighted by the green and yellow. The interior of the object is usually finished with a coat of red, orange or brown lacquer derived from the hin-thabada colorant. It takes approximately four to eight months to complete a fine piece of lacquerware. T he averages object must pass through about twenty-six separate processes altogether. For specially commissioned work, production can take up to two years. The price of a lacquerware object varies according to the amount of time and effort invested in decorating it.

The traditional yun decorative technique reaches its highest development at Pagan. It is also practiced at Laikha in the Shan States, and at Kyauk-ka in Upper Burma.

Inspired by the more restrained aesthetics of Far Eastern Lacquer, European residents at the turn of the century commissioned black lacquerware where incisions were made to expose the grayish matt finish of the immediate priming coat, which presented a subtle contrast to the shiny black surface. Sometimes these ware where further highlighted with lines of gold paint with pleasing result. The majority of these early examples appear to have come from Kyauk-ka in Upper Burma.

In the 1980s there was a revival of interest in these wares amongst lacquer workers. Attempts were made to create a 'satin damask' finish through the painting of large floral and vegetal designs in shiny lacquer on a Matt ground, highlighted by the odd sketchy incision. The results by and large were less than satisfactory. This bold new careless style did not appeal to regular purchasers of lacquer (the Burmese housewives) and lacked the meticulous finish to widely appeal to a foreign clientele. In the 1990s workers at Pagan returned to the original method of detailed incising against a hatch stroke ground to highlight the underlying Matt surface with more promising results. These understated but intricately incised wares have become popular with Japanese customers.

Green WaresGreen colored wares incised with small repetitive patterns in black, red or yellow were at one time made in the Shan States, possibly at Laikha. Designs tend to be geometric with circles predominating, which were often highlighted by dots of yellow, or gold. Green wares depicting figural elements are comparatively rare. Antique green wares of darker almost blackish hue incised motifs in yellow were made at Pagan from mid to late nineteenth century. Unfortunately, the art of making such wares appears to be lost to posterity.

White WaresThe introduction of yun lacquer designs in black, red, and green against a thick yellowish white ground was an innovation brought from Japan in the 1950s by U Tin Aye, a former principal of the Government Lacquer School, Pagan. However, a shortage of the vital white pigment in Burma has prevented the widespread incorporation of these wares into the Pagan lacquer workers' repertoire.

New Colors and Quicker ProcessingBecause traditional yun ware is subjected to many processes, alternating with spells of drying in the cellar, it is very time-consuming to make and relatively expensive for most Burmese. Since the seventies, lacquer entrepreneurs have been seeking ways to produce attractive serviceable lacquerware by shortening, combining, and in some cases eliminating altogether, a number of the tedious processes associated with the making of incised wares. Since there is little that can be done to shorten the process of preparing the surface of an object without severely compromising the quality and appearance of the final product, lacquer workers have looked to decreasing the time spent on applying various colors to an object.

With the endemic shortage and increasing prices of raw materials needed to make traditional colorants, lacquer workers began experimenting with oil-based enamel paints, which were readily available on the black market at affordable prices. Kyauk-ka in the Mon-ywa area during the late seventies led the way by producing gaily decorated everyday wares in fresh bright color out side the traditional conservative palette on a shiny black ground. On these wares the entire design was first incised into the surface of the object. The incisions were then filled with enamel colors-white, yellow, orange, and brown-applied in broad horizontal bands or daubed over an area, regardless of subject matter, so eliminating the traditional multiple drying processes. Because enamel paints are thicker than the traditional colorants, the designs could not be rendered in the intricate detail associated with classic yun work. These bold colorful folksy wares continue to be popular in Upper Burma, but due to transportation difficulties they are rarely exported to other parts of the country.

Pagan artisans, who were initially disdainful of Kyauk-ka's efforts to simplify the yun the lacquerware process, in the late eighties came up with a regressive process of their own using commercially produced enamel paints. As with Kyauk-ka, the object to be decorated has the whole design incised into the surface prior to the application of the first color. The predominant color (which is often a blue enamel.) is applied and then sealed with quick-drying glue from acacia (Acacia farensiana). Any excess pigment and glue is quickly removed. The second color is added immediately and the process repeated. Up to three colors can be applied in a day, so eliminating numerous time-consuming drying and smoothing processes. Such wares in addition to blue include a palette of green, yellow, pink, and red. Although popular with tourists, Burmese connoisseurs generally shun such wares, for the enamel pigments are not as durable as those prepared by traditional methods. Pigments on objects subjected to regular dairy use have a tendency to fade and rub away after a few months. The palette also displays an aesthetic, which is alien to traditional Burmese taste.

Unlike most producers of Asian lacquer, Burma traditionally has not made widespread use of painting techniques to decorate lacquerware. The Shan, inspired by the painted wares of their Tai compatriots in northern Thailand, have traditionally embellished everyday objects of basketry and wood by painting simple repetitive geometric patterns and semi-abstract motifs in red and black lacquer. The designs on some show similarities to wares of the Yi people of southwest Sichuan. Various boxes, carrying baskets, and small tables are among the items decorated in this way.

Encouraged by the Department of Cottage Industries, Kyauk-ku during the colonial period began embellishing formerly plain black everyday wares with oil-based paints in white, pink, green, and yellow on a black ground. Subject matter consisted of European-inspired floral sprays and birds rendered in a bold careless manner using color loading and brush manipulation techniques adapted from Chinese painting. Such wares continue to be made to this day. Today painting is commits practiced in conjunction with incised work. The perimeter of the decorative area may be different by series of parallel-incised lines around a central painted motif.

Since the early nineties simple 'scenes of Burma' rendered in oil colors overcome minimal incising on highly lacquered plaques of different sizes have been produced for the tourist trade.

Marbled Lacquer Japan YunThe technique of making marbled lacquer was introduced to Pagan lacquer workers by the late U Tin Aye, former Principal of the Lacquer School at Pagan, who was sent as State Scholar to Wajinam in 1954-55 to study Japanese methods of lacquer decoration. While in Japan he studied a number of new techniques, many of which unfortunately, could not be introduced into Burma due to the non-availability of critical materials. One technique which was relatively easy to learn and for which materials were readily available, was that of marbling. It only required aluminum or silver paint and lacquer. The earliest evidence for marbled lacquer dates back to Tang Chian period (AD 618-906) where it came to be called his pi, because of its surface resemblance to the wrinkled skin of a rhinoceros or the worn surface of a leather saddle. Referred to as byakudan-nuri or tsugaru-nuri, this technique has been know in Japan since the sixteenth century Muromachi period when gold and silver foil designs were coated with lacquer to impart a mellow finish to an object (Lee 1972: 222).

Marbling came to be called Japan yun by lacquer workers in honor of the source of its introduction to Burma. In this process the surface of an article is initially prepared in the usual way and a design is lightly etched onto the lacquer base. The design surface is then coated with five to ten alternating layers of silver speckled patterns. Although figurative motifs are possible, the majority of designs favored by Burmese craftsmen are strongly geometric in form.

In Burma, Japan yun is made primarily as a cheaper ware for the tourist trade. The majority of objects ten to be roughly fashioned and the plain undecorated interior lacquer surfaces are not always well finished. The use of finer sifted materials for the underlying surface and more careful attention to detail throughout the production process would improve the quality of these wares. Boxes and bangles embellished by this technique are popular with tourists.

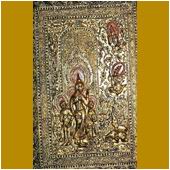

Gold leaf Lacquerware Shwei-zawaThe production of lacquerware embellished with gold leaf designs is referred to as shwei-zawa in Burma. The act of gilding has always been associated with the performing of a meritorious deed and its use in relation to lacquer was at one time limited to royalty and religious donations.

It is very likely that Burma acquired the technique of gold leaf lacquer from Thailand, the leading exponent of this art form in Southeast Asia. The earliest known Thai gold leaf wares (lai rod nam) were made in the capital of Ayuthaya in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries (Garner 1979:265). The conquest of Ayuthaya in 1767 during the reign of the Burmese King Hsin-hpyu-hsin (r.1763-76) caused many artisans to be taken captive to Burma. So successful was this sieges that virtually poets were taken en masse to Burma. This infusion of new blood led to a flowering of literature and art in Burma under Kon-baung court patronage (Htin Aung: 1967: 175).

The art of gold leaf lacquer was practised in Prome and Mandalay in nineteenth century Burma (Fytche 1878: 313). One famous craftsman, Hsaya Hpa who was known to be working in Prome c. 1916, was singled out for special mention by European travelers to Burma and was a recipient of prizes at the Indian Art Exhibition in Delhi that year. His work has been praised for being 'bolder in design and consequently more attractive in many ways than the finikyh desighs from Mandalay' (Moriris 1919: 9-10). Prome was especially noted for its gilded scripture chests embellished with scene from the Life of the Buddha, the Ramayana epic, and Burmese folktales.

By 1919 the art of gilded lacquer had died out in Prome, and apart from the making of kammaqa-sa religious manuscripts, very little shwei-zawa work is currently being done in Mandalay. The few surviving examples that can be attributed to Prome possess a lively elegance and a sureness of craftsmanship, which is not always seen on more recent work. Unfortunately, delicate gold leaf patterns do not stand up well to wear and tera. On many nineteenth century examples the details of the designs have worn away.

Pagan is the present-day center for this art. Most of the items decorated in the yun technique (bowls, plates, vases, and boxes) may also be embellished with gilded designs.

The Gold leafing Process

Compared with the painstaking methods required for incised decoration, shwei-zawa is less time-consuming, but requires a high degree of artistic skill on the part of the craftsman.

The surface to be gold-leafed is prepared in exactly the same way as for incised decoration. The object is formed and receives several coast of lacquer until it has acquired a lustrous, smoothly polished surface. Two slightly differing methods may be applied to produce gilded decoration.

The most common process, which is used when a predominately gold decoration is desired, is the negative design technique. The craftsman, using a pen with a very fine point, carefully paints in free hand the outline of a design with a water-soluble of yellow orpiment and neem gum. He paints only those parts of the design on which he wishes to reign the original lacquer color (usually black, but occasionally red or orange). The area to which the gold is to adhere is left unpainted and is a negative of the design. A thin coat of lacquer is applied to those portions of the design, which are to be covered with gold leaf. Thin squares of gold leaf are then spread over the entire area and pressed onto the surface with a swab of cotton wool.

If the gold is to adhere successfully, great care must be taken at this stage to keep the surface completely free of grease and oil. Even a misplaced fingerprint will be visible on the final design. After drying for approximately twenty-four hours, the object (which is still slightly tacky), is washed in water. Excess gold leaf applied over the orpiment solution washes away along with superfluous lacquer, gum, and coloring matter. This allows the shiny lacquer background to show through. As if by magic, the intricate gold leaf design emerges simultaneously in all it s glory. The object is then returned to the cellar to complete the hardening process (Khin Maung Gyi 1963: 18). The water in which the object was washed is filtered to reclaim the excess gold leaf for future reuse.

When a relatively small area (such as a central medallion on a box, or the highlights in a painting) is to be decorated with gold leaf, the artist creates a positive design by drawing a sketch on the area to be gilded. It is then covered with a coat of lacquer and the gold leaf is pressed into the sticky surface. When the object is nearly dry, the excess gold leaf is washed away to reveal the details of the design (Markert 1979: 44). Because of the special artistic skill s required to roduce gold leaf designs, artists who perform this work are among the highest paid in the lacquer industry.

As with incised lacquer, gold leaf wares have also been subject various innovations. Blue and gold wares became popular during the colonial period. Tradition asserts that a Frenchman (who remains anonymous), commissioned a complete dinner service with a matt blue lacquer surface embellished with a Burmese chin-thei lion at the center surrounded by a band of Chinese-in-spired fret type patterns and finished around the edge with a plain gold rim. Other lacquerware establishments to sell to foreign tourist eventually copied these pieces. Boxes and flower vases have also been seen embellished in this technique, many of which appear to be older than those with the chin thei design. Because the blue does not adhere well to the underlying surface, on many of the older wares the underlying black base-coat is clearly visible.

To give a greater depth, texture, and surface contrast to gold leaf designs, into late seventies and early eighties it became popular to incise the main motifs with an array of hatch-strokes prior to the application of gold leaf. Because of the textured surface, the gold surface is not as reflective as those of traditional shwei-zawa wares. Around the same time shwei-zawa artisans in the workshop of U Ba Kyi also began experimenting with creating pictorial plaques embellished with effigies of Burmese temples and genre scenes, rendered in the style of a European etching.

Combination WaresThe idea of combining the use of gold leaf and /or surface paint with yun decoration appears to have been developed during the colonial period but seem s to have declined in popularity prior to World War II. Chiang Mai lacquer entrepreneurs revived the technique in the early eighties when reproducing 'Burmese' lacquer objects for the tourist trade. Here were to be found the odd yun-decorated object, with the heads of central characters of a scene highlighted by glistening gold leaf which looked a little strange amongst the more subdued palette of browns, reds and greens on a black ground. The technique was eventually adopted by a few workshops in Pagan that used gold leaf to highlight a predominantly orange, red, and brown palette with more pleasing results. Lacquerware samples of this technique may be seen at the Government Lacquer School at Pagan. This combination technique has not become popular or widespread amongst yun lacquer workers.

As previously noted, lacquer resin when combined with the finely sifted ashes of teak wood sawdust, pulverized bone, rice husks or cow dung, becomes a thick filler paste (thayo). Applied in successive layers, it forms the underlying base for the application of incised and gold leaf decoration techniques. Thayo, however, when prepared from heated lacquer mixed with the pulverized ashes of cow ding and then kneaded until thick and smooth, is transformed into a fine plastic putty with a wax-like consistency that readily lends itself to manipulation (Tilly 1901:11). This pliable substance tenaciously adheres to paper, basketry, wood, stone, and metal surfaces in the form of two-dimensional relief patterns (Burney 1832:175-6).

Relief-moulden lacquer as decorative technique was first developed in china where it was called tui-hung. Examples dating from the seventh to eleventh centuries AD have been recovered. This technique, however, never became widespread their and seems to have been largely abandoned by early Ming times in favor of carved lacquer (Garner 1979: 270, figs 22-4). At some juncture this technique spread to Southeast Asia and reached a higher standard than was originally achieved in china. Relief-moulded lacquer reached its highest development in Burma and has been described by one authority as 'the most aesthetically satisfying work produced by the Burmese sculptor' (Rawson 1967: 200). At this point, it is not known how Burma acquired the relief-moulded technique of lacquer decoration. The technique is also known in Thailand where it has been popular in architectural and furniture decoration. Like gold leaf decoration, the relief-moulded technique might well have come to Burma via Thailand.

Technique of Relief-moulded lacquer

As with the previous methods of decoration, the surface of an object to be embellished with thayo must be specially prepared by leveling and filling all crevices with the usual mixture of row lacquer, powdered sawdust, and a glue fro9m boiled rice. Once the surface is completely smooth, it is ready for decoration. Occasionally the surface may be reinforced with a layer of muslin or tulle-like cloth imbedded within the upper priming coasts of lacquer.

A plastic thayo compound made from heated lacquer and cow dung ashes is prepared and rolled into long vermicelli-like 'threads' which are lightly sprinkled with fine powdered ash to prevent sticking. With the help of an iron stylus, these 'threads' are laid from left to right on a lacquer-coated surface to demarcate the main design areas with raised decoration that serve as a guide for the placement of the more complex motifs that follow. Such motifs may be first sketched on paper and then lightly etched into the surface of the object. Most craftsmen are so familiar with the traditional patterns that this step may be omitted. Artisans work seated on the floor beside a small moulding board, and with the help of a small horn-shaped knife (than-lef), they deftly fashion the thayo into sprays of flowers, small figures, and elements of architecture. For repetitive ornaments, slate and metal moulds may be used. The mould is first lightly powdered with ask before the thayo is pressed into the design. When complete, the decorated area is painted with a further coat of lacquer to make sure that all elements of the raised design adhere firmly to the object (Hla Aung 1959: 194-5).

The thayo remains pliant for a couple of days, after which it becomes quite hard and assumes the appearance of polished ebony. In the finest work, thayo designs look virtually identical to two-dimensional woodcarvings and are in some ways superior. Having no grain, thayo moulding is less liable to fracture. Unfortunately, with age thayo does have a tendency to separate from the surface of the object (Morris 1919: 10). Broken pieces, however, may be easily reattached with liquid lacquer

Mandalay is the present-day center for relief-moulded lacquer. A little is also produced in Likha and Kyauk-ka.

Thayo relief moulded designs are often highlighted with fragments of colored mirror glass and mica cut into various shapes, a technique which appears in south-East Asia to have reached its highest development in Burma and Thailand. The process of placing glass fragments into the thayo design in Burma is referred to as hman-zi shwei-cha. Like lacquer techniques in general, it is not known how this inlay technique was introduced or evolved in Burma. Harry Tilly and John lowly in separated publications have suggested that this technique was either introduced from Thailand during the eighteenth century or was given a fresh impetus as a result of the wars between the two countries at the time (Tilly 1901: 2-3: Lowry 1974: 41). In the light of the renaissance in Burmese literature and art which followed the conquest of Ayuthaya in 1767, this supposition is reasonable. Lowry is also correct instating that glass inlay become a very popular medium of artistic expression in eighteenth century Burma.

TechniqueA cardboard stencil of the design is made in the workshop. The small fragments of mica, mirror, and colored foil-backed glass are cut into the desired sizes and shapes with a glazier's diamond. The glass fragments are then arranged on tray and lacquered on the back with thitsi and a thayo of sawdust before being pressed one by on into the desired position, often demarcated by strings of thayo. After all the glass has been laid according to the dictates of the design, any remaining gaps are filled with thayo. The object is next given a further coat of lacquer, which is allowed to dry (Tilly 1901:12). The surface is then smoothed and leveled in readiness for the gold-leafing process, with is similar to that previously described for shwei-zawa work.a coat of lacquer is applied over the exposed thayo areas and the object is completely covered with gold-leaf which is allowed to partially dry. Once the lacquer becomes tacky, the object is washed and the gold-leaf peels away from the glass mosaic, adhering only thayo (Myat Daung 1964:14-15).

The earliest know example of hman-zi shwei-cha work set in thayo so far recovered is the cover of a palm leaf manuscript with a date equivalent to AD 1790 which falls within the reign of King Bo-daw-hpaya (1782-1819). The green, yellow and opaque with glass decoration which is very thick chunky, has been fastened to the wooden cover with a thick paste of thayo and further grouted together on the surface by small bands of gilded thayo surrounding each fragment. In earlier examples of hman-zi shwei-cha work the glass, which is cloudy and frosted in appearance, is also thick and roughly cut. Strings of thayo on the surface of the object bind the glass fragments together.

Occasionally one sees a ground of colored glass mosaic which has been overlain with gilded thayo lacquer embellishment. This technique, popular in Thailand may be seen embellishing some monasteries and pagodas of the Shan Stateds.

During the Mandalay period (1857-1885) the glass fragments gradually became smaller and finer. This was probably due to the introduction of improved cutting tools from Europe. The use of mirror glass in natural, pink and emerald colors became popular, while the use of opaque glass declined. Haman-zi shwei-cha work of this period rivals European rococo for their clear strong lines, complemented by delicate modeling. The fragments of glass inlay; the relief-moulded work appears heavy and the designs indistinct. Glass-inlay work is currently practiced in conjunction with relief-moulded lacquer in Mandalay. A little commissioned work is also undertaken at Pagan.

'Disco Gold-leaf'In the late seventies, Japanese gold foil with an adhesive backing was introduced into Burma,. Sold in plastic backed rolls and popularly called 'disco gold-leaf', it has become the prevalent material used for gilding the more cheaply produced hman-zi-shwei-cha decorated wares. Not unnaturally, gold foil owes it popularity to its cheaper price and ease of application compared with the use of the labor-intensive method of using delicate tissue-thin squares of gold leaf. Foil can be easily cut with a pair of scissors according to the size of the object being embellished. However, being thicker, some of the sharpness of the original thayo patterns becomes obliterated by this modern gilding method. To the purists, the harsh glitter of the orange hue of the foil cannot compare with the bright luminous glow emanating from the mellower gold leaf.

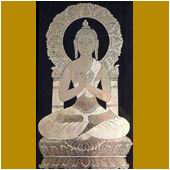

The previously described thayo mixture may also be used to model objects in the round using the dry lacquer technique. Buddha images are the chief objects to be fashioned in this medium (Williamson [1929] 1963:145-6).

This technique undoubtedly came to Burma from China where it has been used for tomb receptacles since the first century BC and for making Buddhist figures since the sixth or seventh century AD (Garner 1979:34 and 49). As with other lacquer techniques of Chinese origin adopted in Burma, the time and mode of transmission is not known. Nor is there any conclusive evidence to suggest that Burma received the dry lacquer technique via neighboring states for this technique does not appear to have been popular in Thailand or Laos. Wood and bronze have generally been the preferred media for religious sculpture in there countries.

During the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the making of dry lacquer images was centered on a number of small villages thirteen kilometers west of Ye-u in the Shwei-bo district. They included Me-O, Shin-the-mye Ma-lwe, and Leni-daw 9Williamson [1929] 1963: 145). The craftsmen who made these images were not professionals; they were farmers who fashioned them in their spare time. A man could turn out thirty to thirty-five images in a season. These images were largely made for a clientele in the Shan States.

TechniqueA rough form of the image was first shaped from well-kneaded clay over the strength branch of set-han-ya-thi, the yellow oleander (Theretia peruviana) sued as armature. The main features were then moulded into place with a wooden or iron knife (than-let). A wash of straw ash and water was then daubed over the image before it was completely dry. A thin casing of cloth soaked with lacquer at this juncture was probably wound around this clay core. A plaster of thayo mixed with teak sawdust was applied over the clay until it was about one centimeter thick. Using the indispensable than-let, important elements such as the main folds of clothing, facial features, and hair were added to render the stature correct in every iconographic detail.

On hardening, the inner clay core was flushed away by washing. For less accessible areas such as the head and the arms, the image was cut open to remove the more stubborn remnants of clay. The openings were then resealed with a thayo of thit-si and sawdust. After resealing, the image was given a htin fine coat of filtered lacquer mixed with the ash of straw or bran. The final details were then worked upon with the aid of the thanlet, before rubbing smoothed the statue with a stone lubricated with sesame oil. Once the image had hardened, it was rewashed and polished in readiness for the final coat of the3 highest grade brown or black lacquers (Williamson [1929] 1963: 146). At this juncture relief-moulded thasyo and glass inlay might be applied for further embellishment. Gold leafing, if desired by the purchaser, would take place at this point. The donor's name and pious aspirations might also be added as an inscription on the base.

The majority of images were made from November to February during the 'cool' season when there was a lull in agricultural activities. This period provided the best conditions for drying both the lacquer and the clay core. If the weather was too hot, the clay core would cry faster, but the lacquer would crack.

Conversely, during the wet season the lacquer would dry well, but not the clay core.

One of the most famous images to be made of dry lacquer was commissioned by King Min-don (r. 1853-78) for the Atumashi Kyaung (monastery), one of the monarch's chief works of merit in Mandalay.

In the building was housed, on a richly gilt pedestal, a huge image of the

Buddha with dimensions prescribed in the Buddhist scriptures. It is a manhpaya

or a hollow lacquered image, made of the silken cloths of the king, covered

with lacquer and gold foil. In the forehead of the image was studded a beautiful

and precious diamond weighing 32 ratties which was Presented to King Bodhawpaya

[Bo-daw-hpaya] (r.1782-1819), (who was King mindon's great grandfather) by the

Mahamanawrahta, the Governor of Rakhine.

(Khin Maung Nyunt 1997: 79)

The practice of making dry lacquer images in Burma seems to have died out during the late twenties possibly due to competition from small cheap marble images from Mandalay and from pictures of the Buddha painted on glass made in Rangoon (Than Tun 1980: 32). However, there are still a number of craftsmen able to do excellent repairs on damaged dry lacquer images with a traditional thayo of sawdust and lacquer.

| Lacquerware Objects for Secular Use |

The Ubiquitous Betel Box

Snack and Cheroot Boxes

Plates, Trays, and Tables

Bottles, Bowls, Urns, and Scoops

Storage Boxes and Cylinders

Lacquered Basketware

Weaving Implements

Musical Instruments

| Lacquerware for Religious and Ceremonial Use Votive Food Receptacles |

Monks' Alms Bowl

Hsun-ok

Pyi-daung and A-wut Khwet-ban

Presentation of Gifts to Monasteries, Pagodas, and to Important Personages

Kalat and Jaung-lan

'Royal Accoutrements': Ceremonial Betel Leaf Holders and Boxes, and Goblets

Monks' fans

Votive Vases

Storage and Production of Sacred Texts

Manuscript Chests Sadaik

Lacquered Books Kammawa-sa

Buddha Images

Furniture

Thrones and Shrines for Images

Preaching Chairs, couches, and Palanquins

Architecture

khmer statue:thai handicraft:asian handicraft:tantrism:Handicraft thailand:buddha antique:bronze buddha