Lai rod nam

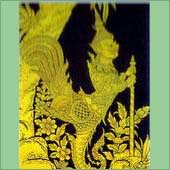

While basic lacquer manufacture is mainly associated with the north of the country, the highly evolved technique of gilded black lacquer, known as lai rod nam or 'design washed with water' in Thai, was a product of the capital cities. It was at its best in Ayutthaya in the 17th - mid18th centuries, and in Bangkok from the end of the 18th century.

The basic lacquer surface is first polished to a perfect sheen. The design-eventually rendered in gold leaf-is painted onto the surface with a resist, or horadarn ink, just as batik patterns are created, The resist is a sticky combination of makwid gum, sompoy solution and a mineral. The design outline is usually drawn onto a sheet of paper, which is then placed over the lacquer. The outline is pricked gently with a needle to create a row of dots; a bag of ash or chalk is pressed over these dots and the paper peeled away to leave a removable trace. The resist is then applied to the areas that will become the clear background-that is, the reverse of the image.

The whole area is next coated which is allowed to dry to the point of being sticky delicate, finely beaten gold leaf is laid down over the entire surface. After about 20 hours, the work is gently washed with water: the horadarn ink absorbs the moisture, expands, and causes the gold leaf above it to become detached, leaving behind the gold leaf applied to the lines and areas between the resist. Since this process did not always work perfectly the first time, a considerable amount of retouching was needed.

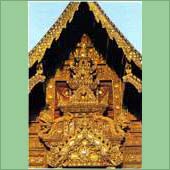

Some of the finest examples of Ayutthayan gilded lacquer work are seen on manuscript cabinets. The detail on right from a cabinet door shows two mythical lions at play in a forest; it is also from that period. The scene above, from the Inner Court of the Grand Palace's from the Rattanakosin period and shows an asurawayapak, a creature with the lower body of a bird and the torso and head of a giant (a variant on the better-know kinnorn:half bird-half man), standing in the Himavamsa Forest.

Ironically, while the technique of gilding lacquer cam from Chin, it was Chines art that was responsible for the decline of standards in Thailand. As professor Silpa Bhilasri points out, the two conventions were incompatible, as Chinesedesign treated spatial elements in a three-dimensional manner. Yet, during the early 19thcentury, the popularity at court for things Chinese encouraged the introduction of this Chinese form of expression, to the detriment of the two-dimensional, complex This art.

Lacquer ware

The manufacture of lacquer receptacles Is among the most important traditional crafts in Thailand, being part of an almost 3,000-year Asian tradition which most likely originated in China, In its basic form, Thai lacquer ware is undecorated and highly functional, although its inherent beauty may disguise its utilitarian nature. Well-applied lacquer has a remarkable range of characteristics; it is light, flexible, waterproof and hard; it also resists mildew and polishes to a smooth luster. Indeed, it has many of the qualities of some plastics, but with the advantage of being a naturally evolved product from local materials.

Lacquer in Southeast Asia comes from the resin of Melanorrhea usitata, a fairly large tree that grows wild, up to an elevation of around 1,000-m (3,000 ft) in the drier forests of the north. It is similar to the Sumac tree of China and Japan, Rhus Vernicifera.

In Thai, Lacquer ware is called kreung kheun (kreung in this case meaning 'works'), which hints at its origins. The tai Kheun are an ethnic Tai group from the Shan States in Burma; after the 1775 re-capture of Chiang Mai from the Burmese, the new ruler, Chao Kawila, forcibly moved entire villages from the Shan States in Burma to re-populate and revitalize the city. This kind of re-settlement after victory was a common practice then, and craftsmen were particularly valued. One community of lacquer workers settled in the south of the city and their name became synonymous with lacquer.

Although lacquer is often applied to wood, its original us was over a carefully made wicker-base structure: this brings forth two of its finer qualities-lightness and flexibility. In fact, with a well-made bowl it is possible to compress the rim, such that the opposite sides meet, without cracking or deforming it.

The process is time-consuming. The form is first made using splints of hieh bamboo; their width and thickness must be appropriate to the object size. If they are too big, the gaps between them will be too wide to take the costing of lacquer. The best time for applying lacquer is supposedly the end of the rainy season, when the atmosphere is moist but not too hot. The resin is applied in a number of layers, each of which must be completely dry before the next coat is applied: the entire process can take up to six months. The resin, or rak in Thai, has varying admixtures at different stages. The first layer is often mixed with finely ground clay so as to fill the gaps in the wicker-work, while the last and finest layers are mixed with ash, from burnt rice, bone or cow dung.

Once each layer is dry, smoothing occurs, using various materials at different stages, including dried leaves, paddy husks and teak charcoal. Finally, the finished piece is polished wit oil. The natural color of lacquer is black; the re finish characteristic of Shan-style lacquer ware from the North is derived from ground cinnabar, for the best quality (now rare), or the less intense red ochre, which tends to flake.

The oval box below has a rustic inlay of bamboo wedges in the shape of a flower; the eight wooden nested bowls have a decorative mother-of-pearl rim. But the heights of decorative technique, practiced future south in central Thailand, for the court and major monuments, are in the gilded lacquer and mother-of-pearl ware.

Mother-of-pearl ware

A craft that probably developed in Ayutthaya as early as the mid-14th century, and which the Thais practice in a distinctive style, is mother-of-pearl inlaid into black lacquer. It is painstaking work: the individual elements are very small and lacquer embedding involves many appellations. Yet the best Thai craftsmen have gone to extremes, not Just of intricate detail, but of scale of the finished objects. The best-known examples, remarkable in their execution, are the doors of the ordination hall or ubosot at Wat Phra Kaeo, the Temple of the Emerald Buddha, at the grand Place in Bangkok. From a distance they display a coherent decorative design, yet close up the decoration resolves into intricate miniature scenes; as the scale changes, so does the part played by the shifting nacreous colors. This is a hallmark of fine mother-of-pearl inlay.

The mother-of-pearl is the nacreous inner layer of the shell of some molluscs, including oysters. As with pearls, the luster is from the translucency of the thin lining, while the play of colors is caused by optical interference. Thai craftsmen favor the green turban shell found on the West Coast of south Thailand for the density of its accretions, but because the shell is naturally curved, it must be cut into small pieces in order to assemble into flat inlay work. Even then, the pieces must be ground and polished to flatten their edges. Working with large numbers of; small pieces of shell inevitably complicates the assembly process, but it also stimulates the intricacy characteristic of inlay work.

The design is first traced onto paper. Next, the outer surface of the shell is removed by grinding, and the remaining mother-of pearl sections are cut into pieces generally no languor than 2.5cm(1 in). These pieces are honed with flint or a whetstone to reveal the color, and then temporarily glued to a wood backing or a V-shaped wood mount, ready for final cutting. The design is transferred to the shell by tracing paper, which is then cut into individual pieces with a curved bow saw,. Removed from the wood mount, the edges of the mother-of pearl pieces are filed smooth to fit, and pasted facedown into position onto the paper that carries the design.

The embedding process then starts: several layers of lacquer are applied to the object to be decorated. While the last layer is still sticky, the assembly of mother-of-pearl pieces on their paper backing is pressed down onto it, paper side out. Once the lacquer is completely dry, the paper and paste are washed off with water.

There still remains a difference in the level between the mother-of-pearl and the lacquer, so the intervening spaces must be filled in with repeated applications of a mixture of lacquer and pounded charcoal (from burnt banana leaves or grass) known as rak samuk. After each application, the surface is carefully polished with a whetstone and a little water, and allowed to dry; the process continues until the mother-of-pearl is finally covered. After though drying, the surface is polished with dry banana leaf and coconut oil until the mother-of-pearl appears perfectly and smoothly embedded.

Not surprisingly, such a laborious technique is used nowadays. Modern designs are less complex, and the mother-of-pearl is glued directly to the usually wooden surface of the object. Black tempura and filler are then used for the embedding: lacquer is often not involved at all. The pieces here, including the tieb, a receptacle with a cone-shaped cover used for offering food to monks, are, however, from the old school-magnificent examples of the Rattanakosin period.

Celadon is named after a character in Honore d'Urfe's 1610 play, L'Astree, a shepherd who wore a light green cloak with gray-green ribbons. Nowadays the name is used to describe particular type of (mainly green) stoneware. The hue most popularly associated with the name is a pale willow green, but in fact it ranges from dark jade to white, with grays, yellows and greens in between. The precise color depends on the clay, the glaze, and the temperature and conditions in the kiln, which is high-fired to around 1250 degrees centigrade in a reduction atmosphere. As one-authority notes: " There has been a recent move to call celadons 'green-wares'. This is to be deplored as many celadons are not green and many green wares are not celadons.' It is also worth nothing that some modern chemical glazes that use copper or lead are not celadon.

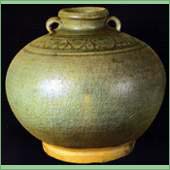

In china, where it originated, it is still called green ware, and the subtly glazed classics of the technique are those produced during the Sung (Song Dynasty (AD 930 to 1280). Some believe them to be the finest high-fired pottery ever made, on both technical and aesthetic grounds, and they have always been difficult to reproduce. Nevertheless, it was one specialty of the Sangkhalok kilns. Their best output is colored a beautiful sea-blue-green, and the glaze is usually rather shiny and glassy and much crazed. Since celadon glaze is difficult to control as it melts at a critical point, it was often not applied all the way down to the base, to avoid problems of it sticking to the support.

Celadon was re-introduced into Thailand from Burma at the beginning of the 20th century, and has since then, in fits and starts enjoyed considerable export success. The center of production is the northern city of Chiang Mai, to where Shans moved across the border on a number of occasions as part of re-settlement programs. The Shan potters, who appear to have come from Mongkung in the Shan States, settled near the Chang Puak Gate in 190, and began producing basic ceramic wares like pots and basins, with a rather dull gray-green celadon glaze.

Later, in 1940, when Chinese celadon became difficult to find, the Long-ngan Boonyoo Panit factory opened a little to the north of here, using the skills of the Shan potters to make household crockery. Although it lasted only a few years, it was followed by other operations, and eventually by the Thai Celadon Company, since 1960 other factories have opende, porducing-varying qualities of output. It was common, even in Sung Chian, for there to be a slight crazing in the glaze, and even though an increase of just a few percent in the silica content would have avoided this, the network of widely spaced lines contribute aesthetically to he depth of the glaze. The jar with ring handles on right is a Sangkhalok ware with cracked celadon glaze. The range of wares that the several factories now offer has expanded to include blue-and-white, and also white, brown and bright blue monochromes, but the core of modern Chiang Mai production remains the traditional delicate green celadon.

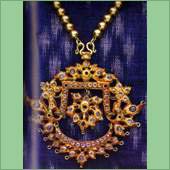

In 1957, pillagers uncovered the country's richest treasure trove: a hoard of gold objects interred in the crypt below the 15th century tower of Wat Ratchaburana in Ayutthaya. Although much had been lost, archaeologists from the Fine Arts Department managed to secure some 2000 pieces, including a spectacular collection of gold regalla, ornaments and jewelry. Now on display at the Chao Sam Phraya National Museum, the jewelry reveals the high level of gold workmanship, and the wealth associated with aristocratic life of the period. The gold button above, is one of these pieces.

The three necklaces shown here incorporate Ayutthayan gold work in modern assemblies and all employ distinctively Thai design motifs. The leaf-shaped pendant, worked in a mixture of repoussee and chasing, is filled with wax to maintain its shape and detail, and is set with a single ruby. As remains customary, rubies (mined on the mainland principally in Burma, eastern Thailand and western Cambodia) were treated as cabochons. Largely because of a regional preference for keeping as much of the weight of a gemstone as possible. The necklace on top left containing alternate gold and glass beads carries a solid engraved pendant representing a bai sema, the leaf-like standing boundary stone that is placed around the ordination hall in a monastery to mark the sacred space. The opaque blue-green beads are of Ban Chiang glass. The third pendant on right, set with roughly faceted diamonds, is notable for its enameling: this technique normally suing the three colors red, green and blue, as here, was developed in Ayutthaya.

The manufacture of gold jewelry, however, did not begin in Ayutthaya. The Khmeres, who controlled large parts of the country until the 13th century, certainly used gold, and pieces have been found at Sukhothai. The engraved slabs at Wat Si Chum in Sukhothai, illustrating the Jataka tales (which relate the previous lives of the historical Buddha), show figures wearing elaborate adornments, including necklaces and crowns. The 1292 inscription attributed to King Ramkamhaeng specifically allows free trade in silver and gold, although the wearing of gold was restricted by sumptuary laws to the nobility, and free use of bold ornamentation was allowed only from the mid- 19th century, under King Rama V.

Ayutthayan work was the high point in the history of gold jewelry. Nicholas Gervais, a French Jesuit missionary writing in the late 17th century was of the opinion that "Siamese goldsmiths are scarcely less skilled than ours.

They make thousands of little gold and silver ornaments, which are the most elegant objects in the world. Nobody can damascene more delicately than they nor do filigree work better. They use very little solder, for they are so skilled at binding together and setting the pieces of metal that it is difficult to see the joints."

Gold work was revived under King Rama I in Bangkok after the defeat at Ayutthaya, and foreign visitors frequently noted the enthusiasm of wealthy Thais for gold ornament. Yet this very enthusiasm may ultimately have played a part in the decline of traditional Thai goldsmithing, for during the 19th century, when King Rama V became the first monarch to travel abroad, a number of foreign jewelers set up branches in Bangkok, including Faberge. Chinese immigrant goldsmiths catered to clients with less refined tastes. The Norwegian traveler Carl Bock wrote in 1888: "The manufacture of gold and silver jewelry, which is carried on to a large extent in Bangkok, is entirely in the hands of the Chinese." Today, it is in the town of Petchabuuri, southwest of Bangkok, that descendants of early master goldsmiths keep the old tradition of gold work alive.

Betel setsThroughout South and Southeast Asia, the chewing of areca nut wrapped in betel leaf, for its intoxicating effect, was (and still is) a custom that transcended class, evolved rituals that helped govern social intercourse, and perplexed foreigners. Early Western travelers saw only effects that were, to them, fairly repulsive: blackened teeth, red-stained lips, and an abundance of spitting those left trails of red splotches on the ground. Yet, from India to the West Pacific, it has been a habit enjoyed by millions for at least 2000 years (that is, form its first documented use in India). The offering of betel was a sign of goodwill to guests; affection in courtship's; and honor at court. The preparation of the 'quid', or a packet of ingredients to be chewed, was considered an essential social skill.

It was indeed the social significance of betel that not only surrounded it with paraphernalia, but also made the latter the focus of varied styles of craftsmanship, some of it of a very high order. The betel set on far right, in gold repoussee, was from the court of Chiang Mai. The open cone-shaped receptacle contained the rolled-up leaves, which, in Thailand, were served folded in this shape rather than as an enclosed packet, as was usual in India and elsewhere. The other boxes housed the sliced nut, lime paste and optional ingredients such as tobacco, shredded bark cloves and various flavorings. The ensemble was usually presented to guests on a pedestal tray, as depicted in the 19th century mural at the monastery of Wat Phra Singh in Chiang Mai on right. The wooden betel tray shown above, lightly lacquered with a decorative inlay of bone, is a more modest item.

There are three essential ingredients in a quid, which combine to create a euphoric effect and are as addictive, if not more so, than nicotine. The first is areca nut, called maak in Thai, an hard seed about the size and consistency of a nutmeg, which grows encased in a white husk and hangs in clumps from the tall, slender areca palm (Areca catechu). There is, incidentally, no such thing as a betel nut: that error crept into English around the 17th century through mis-observation. The betel is actually a green leaf-the second ingredient from a creeper of the pepper family, Piper betle, or phlu in Thai. The third ingredient is lime paste, made from cockleshells that are baked to a high temperature to produce unslaked lime, to which water is added; it is then pounded into an edible paste. Cumin (Cuminum cyminum) is often added to the paste, giving it a red color.

The point of this unlikely sounding combination is that arecoline in the3 nut is hydrolized by the lime into another alakaloid, arecaidine; the later reacts with the oil of the fresh betel leaf to produce the euphoric properties. One side effect is that the saliva glands are strongly stimulated, which accounts from the large amount of spitting. The habit also resulted in the use of the flared, wide-mouthed spittoon, a common item in polite households. The characteristic red color of the spittle and the issuing mouth is due mainly to a phenol in the leaf.

Nowadays, it is more appropriate to use the past tense in describing the betel habit in Thailand, as modernization has largely overtaken the custom. You are much more likely as a visitor to a Thai house to be offered a soft drink than a quid of betel to pop into your cheek, and cigarettes are now generally a more preferred stimulant. In its day, however, betel certainly had its addicts. A German pharmacologist, Louis Lewin-as quoted by Henry Brownrigg in his book Betel Cutters (1991) wrote in the 1920s: "The Siamese and Manilese would rather give up rice, the main support of their lives, than betel, which exercises a more imperative power on its habitues than dose tobacco on smokers."

Gongs

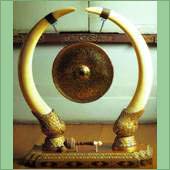

Two elephant tusks support a ceremonial gong on left, in an early Rattanakosin residence. Today, this use would be frowned on, but it should be remembered that in traditional Buddhist Thailand, ivory was usually taken only from tuskers that died from natural causes.

The earliest Thai instruments were made before Indian culture made itself felt, and all had onomatopoeic names, that is, single syllabic words that approximated the actual sound. The gong is one of these, known in Thai by the very similar-sounding khawng. The English word is certainly derived from the Malay gong; the Thai probably also. In a variety of sizes, in different combinations and put to different uses, all gongs have the same basic form: a flat front surface with a raised boss in the center, and a thick circular rim behind, tapering slightly inwards. This rim, called chat after the tiered umbrella that is the symbol of royalty in Thailand, is pierced with two holes, from which the gong is suspended.

This fine example is beautifully decorated in gold with characters from the Ramakien against a typical kanok motif background. Gongs of this size, between 30 and 45 cm (12-18 in) in diameter, make a sound similar to mong in Thai, and so are called khawng mong. One of the several original uses of such gongs was recording the passage of hours, as bells were rung in Europe. In Thailand, however, two different instruments were used: a drum for the night hours and a gong for the day. A legacy of this is the vocabulary in modern Thai for the time of day. Daylight hours, beginning at 7 o'clock, use the word for gong in conjunction with the hour, as in sawng mong chao, meaning 'second morning hour', or 8 o'clock. The 'thum' sound of the drum yielded the expression for evening hours, so 8 p.m. is sawng mong thum. The word for an hour is chua mong-literally the interval of time between the soundings of the going.

Gongs of different sizes had many ritual uses, as in processions, and are still used in some ceremonies. They were also an important percussion instrument in the Thai musical ensemble, the piphat. Groupings varied from a pair (one high-toned, the other low-toned) suspended in small wooden box open at the top, to the circle of gongs, as in the mural painting on right. The player sits inside the circle with a beater in each hand, the gongs arranged clockwise in ascending pitch: the smallest at the far left, behind the player, to the largest at the far right and behind. Considerable dexterity and suppleness is needed to play them.

Votive tablets

When the ancient capital at Sukhothai was being excavated by archaeologists (and unfortunately also by illegal treasure hunters), large numbers of small tablets were found buried. Most were of baked or unbaked clay, a few in silver, gold or pewter, all carrying images of the Buddha. They were portable Buddhist icons, and Sukhothai is not the only place where they have been found. They were buried in the most sacred parts of many temple complexes, in caves used for meditation, and inside stupas.

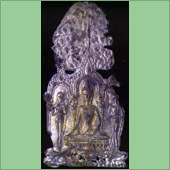

The pictured here are by no means typical. They are from Sukhothai, and each has exceptional qualities. The gilded clay tablet from the Chao Sam Pharaya Museum in Ayutthaya, features an interpretation of the famous walking Buddha that is unusually finely worked for its size. The silver votive tablet also from the Chao Sam Pharya Museum and manufactured by the repoussee techniques, shows the Buddha in the most widely used of all postures in Thailand, bhumisparsa, touching the earth with his right hand upon achieving Enlightenment. Less usually, the sacred bodhi tree under which he is seated is depicted in realistic detail. The third votive piece in near-perfect condition is in gold repoussee, 21 cm (8 in) high and found at Wat Phara Pai Luang, also in Sukhothai. In the U-thong style, from the 15th -16th centuries, it shows a stance unique to Sukhothai and its dependants, with the arms held straight down at the sides. This is popularly known as phara poet lok in Thai, literally 'Buddha opening the world(s)', and refers to the Buddha's descent from the Trayastrimsa heaven, when he opened the three worlds of heaven, earth and hell, so that all beings could see each other.

One of the most interesting aspects of votive tablets is how they developed from being devotional Buddhist objects into the modern cult of amulets. The distinction between the two is not completely clear either, as it is claimed that many amulets sold on the market now are ancient votive tablets. Moreover, while it is difficult to be sure to what use these old votive tablets were put at the time they were made, it is known that many were carried home by early pilgrims visiting sacred sites. In one sense, they could be considered the earliest tourist souvenirs, though within a sacred context.

The practice originated in India. In here book, Votive Tablets in Thailand (1997), M. L. Pattaratorn Chirapravati notes that Chinese monks who visited India in the second century wrote accounts that described the stamping of tablets. Using press moulds, monks made these tablets not only for distribution among the faithful, but also as a meditative exercise.

While souvenirs of a type, votive tablets were and still are considered intrinsically sacred. One practice that was followed, particularly in the south of Thailand, was for the powder from the cremated remains of senior monks and revered religious teachers to be ground up into the clay used for stamping. This undoubtedly contributed to he more recent amulet cult. And fostered the belief that such tablets would contain special powers

Amulets Votive

tablets began as sacred mementos of visits to holy places, but over time went

through a process of change, acquiring, in the minds of believers, the ability

to protect. In the streets around Wat Mahathat in Bangkok, close to the Grand

Palace, pavement stalls sell amulets, which are essentially votive Buddhist tablets

to which are ascribed specific powers. More that this, some half a dozen Thai

collectors' magazines, and even a dealer's web site, specialize in amulets. Amulet

collection in Thailand is now a significant besides, with the rarest items changing

hands for more than a million baht spice.

Votive

tablets began as sacred mementos of visits to holy places, but over time went

through a process of change, acquiring, in the minds of believers, the ability

to protect. In the streets around Wat Mahathat in Bangkok, close to the Grand

Palace, pavement stalls sell amulets, which are essentially votive Buddhist tablets

to which are ascribed specific powers. More that this, some half a dozen Thai

collectors' magazines, and even a dealer's web site, specialize in amulets. Amulet

collection in Thailand is now a significant besides, with the rarest items changing

hands for more than a million baht spice.

It was during the reign of King Rama V, towards the end of the 19th century, that votive tablets began to be treated in significant numbers as amulets. However, there is some evidence that the cult began in the reign of his father, King Mongkut (Rama IV). It is likely that one catalyst was the new popularity of collecting antiques that spread from the court, and because of increasing demand, ancient sites began to be excavated illegally. At first, the clay votive tablets were held in little regard, but gradually their provenance, and the idea that the monks who had created them must have transferred into them some of their power, made them increasingly desirable. By the early 20th century, the cult had become established, although its relatively rapid development is clear from the comments of King Rama VI, who ruled from 1910 to 1925, and wrote: "It is astounding that people hang votive tablets around the necks as self protection." Today, most Thai men cross all classes carry and amulet; women to a lesser extent.

To a casual non-Thai observer, such an amulet may appear to lack refinement, workmanship, and even distinctiveness. However, two essential qualities are hidden: the person who makes it, and its composition. Most amulets are of clay, but this medium is often very complex. Being mixed with a number of unusual ingredients, which contribute to its power, including certain seeds, dried flowers, herbs, pollen, and the ash of burnt sacred texts. Moreover, if a revered senior monk made the composition, it wills benefit from his power.

Two examples of dealers' notes give some flavor of the arcane qualities that amulet collections seek. They describe two of the most famous amulets, Phra Somdej (the name of a famous old monk), and the strange Phra Pid Ta ('buddha with eyes Closed');

"There are only five forms of Somdej Wat Rakank: Make sure you have seen a genuine one before and compare it with other Phra Pim Somdej to spot the differences. Look at the texture and the substance and examine the composition, which has been molded out of burnt limestone and then mixed with Chinese Tung oil and holy matters such as Med Chad, Med Phradhati. Holy Dried Flower, Fried Stream Rice etc."

"Luang Phor Thub (Designated Name is Phra Kru Dhebsit dhepa dhibbodi) is the ninth in order of former Chief Abbot of the Wat, who has created the most revered Phra Pid-Ta and Pid- Dhavarn of Wat Thong in the year BE 2442 (AD 1899). Amulets were created between the years BE 2442 to 2453; the major proportion was Phra Pid-Dhavam: nine human orifices' closed gesture, and the minor proportion was Phra Pid-ta: eyes closed gesture."

Whit rare, sought-after amulets commanding prices in excess of US$20,000, many fakes abound, but even this is not straightforward. Reproductions of famous, costly amulets are common, yet once they have been sanctified by a monk, they will still afford protection to the owner-as long as he or she respects it. And behaves well, according to Buddhist precepts.

Ceramic propitiatory figurines Located

at one end of the courtyard of Wat Ratchanaddaram, across the canal from Bangkok's

prominent Golden Mount, is a small market devoted to amulets and other votive

paraphernalia. There are rows of tiny, mass-produced, doll-like figures, such

as Chinese goddesses, white-bearded sages, King Rama V, fat-laughing Buddha, children

with ancient costumes and hair arranged in the traditional top-knot and strange

creatures with bodies of men and heads of a variety of animals.

Located

at one end of the courtyard of Wat Ratchanaddaram, across the canal from Bangkok's

prominent Golden Mount, is a small market devoted to amulets and other votive

paraphernalia. There are rows of tiny, mass-produced, doll-like figures, such

as Chinese goddesses, white-bearded sages, King Rama V, fat-laughing Buddha, children

with ancient costumes and hair arranged in the traditional top-knot and strange

creatures with bodies of men and heads of a variety of animals.

Despite their gaudy aspect and the cheap material used, the figurines are not toys but propitiatory offerings placed at shrines, spirit houses and temples. The ceramic kilns at Sukhothai and Si Satchanalai fired thousands of similar figurines in the 14th to 15th centuries; the glazed examples below are typical. The colors varied from white to celadon to brown, and black underpinning was occasionally used to emphasize details.

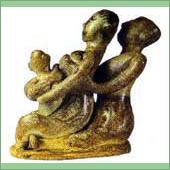

What makes these individually modeled pieces so much more interesting than the mould-stamped modern versions is the love and observation that clearly has been put into them. None are masterpieces, but the work of local craftsmen who draw on their own experience and the life around them to create spontaneous as well as sincere works. The mother-and-child figure, definitely mass-produced from the quantities that have been unearthed, was a particular favorite, and usually lovingly observed. In the woman-and-baby (Sangkhalok ceramic, Wat Mahathat), the mother sits in the polite posture with her left leg bent so that the foot points backwards and the right leg bent so that the foot presses against the left thigh. Her young child stands on here ankle, holding her. In the couple and baby, a man sits hugging his wife on his lap, while she in turn holds the baby; all are encircled in a tight family group (Sangkhalok ceramic, 13-14th centuries, Ramkamhaeng Museum).

Two of the pieces here have been repaired at the neck, but detached heads are also quite common. Such breakage was not accidents, but a feature of their use. When people took a figurine to the temple as a propitiatory offering to solve a problem such as bad luck or ill health, the function of the figurine was to remove the harm or had luck. To this end the figurine's neck was broken and the remains buried. Such broken pieces are known as tukata sia kraban meaning literally 'doll that has lost its head'.

Spirit houses

Animism runs deep in Thai belief, although with out conflicting with Buddhism. Traditional belief systems revolve around the hierarchy of spirits, or phi. The spirits, who have unlocalized, general dominion, are broadly deviled into good and harmful beings. The good, originally known as celestial spirits, or phi fa, later became identified as thep. This comes from the Indian devata, meaning minor divinities, and often inaccurately translated into English as 'angels' (as in 'City of Angels', the Thai name for Bangkok, Krung Thep).

Of most immediate importance to daily life, however, are the territorial spirits, who live with nature and are identified with its physical elements, such as water, mountains, caves and forests. They are not only spirits of place but also masters- jao- of their particular area of the natural environment. As such, they must be propitiated so that the humans who must share the habitat with them will not offend them. More than that, the spirits' help is needed to assure success for the family and the community.

There are in total nine territorial guardian spirits. These are: Protector of the House; Protector of the Gates and Stairways; Protector of the Bridal Chamber; Protector of the animals; Protector of the Store-houses and Barns; Protector of the fields and Paddies; Protector of the Orchards and Gardens; Protector of the terraces; and Protector of the Temples and Religious Establishments.

Traditionally, temporary shrines were erected for ceremonial occasions when the spirits had to be invoked: birth, marriage, death and house building. This practice at house building led to the maintenance of a permanent shrine, because there was always the risk that the guardian spirit of the land, phra phum, would not accept the continued presence of the householder and his family. They were, after all, usurping the spirit by erecting a building and moving in. The full title of the guardian spirit is phra phum jqo thi, the final two words meaning 'master of the place'. A specialist is needed to supervise the siting of the spirit house, to make sure that every aspect is appropriate. If, for instance, it were located in the shadow of the house, the spirit would not give his protection. Daily offerings of a little rice are placed at the spirit house and a special annual offering of pig's head and chicken is given, usually on New Year's Day (this occurs in April in Thailand).

The spirit house generally takes the form of a miniature traditional Thai house, usually with a little porch or veranda on which the offerings are placed. The style is open to interoperation, as these examples show. Are often placed within the tiny house. One specific figure is Jawet, a divinity holding a sword, or a book and whip. The book contains the register of the good and evil acts committed by humans living within the area.

In village communities, the guardian spirit of the land is honored as the phra phum ban (spirit of the village) with a specific (quite substantial) shrine in the form of a small house raised on posts, and located in its own fenced enclosure. Every year, at a special ceremony, the community traditionally offers food and other gifts. This custom is still maintained to an extent, but in the past it was taken very seriously. A British engineer, Holt Hallett, recounts, in his book A Thousand Miles on an Elephant in the Shan states (1988), that when he was there in 1976, the villages were closed off and "forbidden to strangers on the occasion of the sacrifice to the village tutelary spirit at the new year".

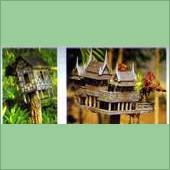

Assembly hall models

Highly prized because so few have survived, models of monastic buildings, in terracotta, wood and cast bronze, date mainly form the Ayutthaya period. These were not architectural models, but votive object presented to the monastery itself. As with Buddha images, evidence from inscriptions is limited to northern Thailand, where it became fashionable to record some information on the base. In the case of the bronze model, 102 cm (40in) tall, displayed at the Chao Sam Phrya Museum, Chiang Mai, we have a short history. A local dignitary of the town of Chiang Saen, and his wife commissioned it in 1726. A model of the viharn, or assembly hall, of Wat Pha Khao Pan, a monastery on the banks of the Mekong River, it was cast and presented in time for the inauguration of the actual viharn.

Until the town's comprehensive destruction in 1804 during fierce fighting to dislodge the Burmese, Chiang Saen was an important center, famous for its monasteries and bronze casting. Donating such a model was, as presenting a Buddha image, an act of merit. This bronze model survived the original building, which either deteriorated because of its wooden construction or, more likely, was burnt down in 1804. In any case, it is an attractive example of northern temple architecture, which differed from that of the Central Plains. The original, however, would probably not have had such a high, tiered base: it is more likely a pedestal for the votive piece.

Most monasteries have several buildings. The most frequently used building is the viharn, a hall for both monks and the laity to gather in. Gabled, and with its principal entrance at one end facing east, the direction of sunrise, its interior is mainly bare save for a pulpit from which scriptures are read, and for one or more statures of the Buddha at its western end. Raised on a plinth or on special tables. A second building of the same general construction is the ordination hall, called an ubsosot, or simply bot. This is exclusively for the monks' use, and is sanctified by its main distinguishing feature: as set of eight markers, around its perimeter, known as bai sema. These halls were often the rooms that the models depicted, as seen by the two wooden models.

The terracotta model, located in the Chao Sam Phraya Museum and Ayutthayan, illustrates another typical feature of traditional Thai architecture-the sagging roof or truss. In Thai this design is called the 'underbelly of an elephant' for obvious reasons. Its popularity ironically grew out of a structural defect of the post-and-beam construction of such buildings: the weight of the beadwork tended to compress the wood vertically. For the most part this was a problem to be corrected, but for a short period it was aesthetically appreciated.

Monk's chairs

These deeps, low monks' chairs, many of which have found their way into domestic interiors, have a specific function. Known as thammat, the chairs are intended for use by monks when preaching or reading the scriptures to a congregation. They are in fact, just one of several designs of the ecclesiastical seat, some of which are elaborate tall structures with tiered spire roofs, others plainer and lower. All fulfil the same role as the pulpit in a church.

The Thai preaching seat has its origin at the beginning of the Sukhothai period, during the reign of King Ramkamhaeng. A 1301 inscription records that a stone throne called Phra Thaen Manangkasila-asna, which the king had built, was used by senior monks to preach from. Since then, three kinds of pulpit have evolved. The oldest, known as a thaen or tiang, and deriving from the original Sukhothai model. Is a simple rectangular seat without a backrest, standing about 50 cm (20in) high. Occasionally of stone, it is more commonly made of wood, with short legs that are often re-curved in to representations of a mythical lion's paws, known as kha singh. This plain style is likely to be found in rural monasteries.

A second style of pulpit has become popular as an item of secular furniture, not just in the West but also in some of the wealthier traditional houses, as in this picture. Known as a thammat tang, it is a development of the thaen in having a backrest and two arms rests. A distinctive feature is its depth; if used in a Western style of seating it needs a cushion behind to support the back. Because the seat was actually a platform and the monk sat cross-legged on it with his feet off the ground, it needed the extra depth. With its 'lion's legs', it may be used directly on the floor, as in the main picture opposite, or raised on a larger accompanying platform.

The most elaborate style of pulpit, and historically the most recent, is the thammat yot, also known as the busabok thammat. A busabok is a tiered reliquary, with a tapering top. For enshrining a Buddha image. This third kind of pulpit takes its name from its similar appearance. The elegant, tall structure is a tiered, wooden tower consisting of a base, body and apex. It looks far more like a Western pulpit than do the simpler seats, apart from the fact that it has a highly decorative appearance, the carved surfaces typically being gilded. The seat is within the body, and accessed by steps at the back or side, either built in or as a separate ladder. Spectacular constructions, they are too large and dominating to be seen outside monasteries.

Monastery drumsThe oldest instruments in all cultures are the percussion, and in most of Asia that means the drum and gong. Indeed, the Thais like the Chinese often refer to the two together in one expression: 'gongs-and-drums'. Naturally, instruments as ancient as these have acquired a range of uses well beyond their roles in an orchestra. In the case of Thai drums, of which there are about tow dozen varieties, many are named after the activity with which they are associated. There are klawng khon, used to accompany performances of the masked khon drama described and klawng nang, used with shadow plays. Drums were used in the past to signal the evening hours, and in most northern monasteries there are drums for regulating activities and for celebrating certain ceremonies.

These monastery drums are the largest in Thailand, and have a highly distinctive, elongated shape, with a single drumhead and a narrow waist flaring slightly towards the 'tail', the very largest can be found in Mae Chaem in North Thailand. It averages 3 m(9ft) in length. Its Thai name, klawng aew, means 'waist drum', and refers to the narrow central section where the two halves join. The resonance chamber takes up half of the length, tapering slightly from the drumhead, which normally has a diameter of about 50-cm (20 in). The skin is held tight by groups of long leather thongs passed through twisted cane loops and secured in the middle of the drum. Just above the 'waist'. The lower half of the drum is a separate hollowed-out cylinder of wood. Carved decoratively to leave a series of protruding rings.

The drumhead, made of stretched hide, is usually painted with a black circle in the center and a black rim around the edge, the paint coming from the sap of a tree. The black circle and rim help to mark the center from the player, while the sap helps preserve the skin. In addition to this treatment, a mixture of ashes and cooked rice is sometimes also applied to the drumhead to adjust the tone and pitch.

The drum may be used for summoning monks to various activities, and also, because of the carrying power of its sound, to call villagers to certain ceremonies, especially in the most notable of events, the annual ordination of young men at the beginning of the rainy season, and at Songkran, the Thai New year. There are drumming contests held in the coolest of the winter months: December and January.

A smaller version of the drum, also used in monastery ceremonies, is the klawng yao ('long drum'), about 75cm (30 in) long, with a cloth strap that allows it to be hung around the shoulders. Both of these drums appear to have been adopted from the Burmese, they are an equally common sight in monasteries around the Shan states of Burma. The story goes that during a lull in the bitter fighting towards the end of the Burmese wars in t he late 18th century, Thai soldiers heard the Burmese playing this long drum, which the Burmese called ozi, and made similar drums for themselves. Another possibility is that Burmese immigrants brought it into the country during the 19th century. Whatever its origin, the drum is now very much a fixture of monasteries in the North.

Old drums are nowadays occasionally sold as antiques and also made into occasional tables; the wooden one shown on far right has been put to sculptural use in a Bangkok garden.

The long drum is not the only instrument that found in monasteries. Bells also play an integral part in monastic life and are used throughout the country. Their ringing, heard across the rice fields surrounding a rural wat, is in its way as evocative as the peals of English church bells. Thai bells, always bronze, are generally much smaller (approximately 30 cm [12 in] wide to one m [3ft] tall, but there is considerable variation in size and shape.

At monasteries pilgrims frequently visit that and worshippers there may be a number of bells, often donated, rung by the faithful as part of their merti-making. Apart from these, there is the bell used by the monks to regulate the day's activities such as the example on far right in Wat Yaang, Petchburi, and on right in a cloister at Wat Phra That Cho Hae, in Lampang. Struck with a wooden baton or pole, this bell summons members of both the religious and lay communities to devotions at specific times of the day. It also tolls the day's end when monks assemble for evening vespers, and is used to indicate the noon hour.

Monks rely totally on the lay community for their food: they collect alms early in the morning. The significance of the midday bell is to remind the monks that they are prohibited from partaking of solid food after noon: only liquid may pass their lips. The one other meals is taken at about seven o'clock in the morning, after alms collecting. The afternoon and evening are given over to religious studies and prayers, and further meals would interfere with the concentration needed for these. The young monks from Wat Haripunchai, shown on left, have assembled for their midday meal.

This restraint is part of a general principle of moderation laid down by the Buddha; the scriptures contain a number of references to this. He said once: "I am restrained in deeds, words and food", and in addressing the King of Kosala: "Discomforts are less for a person who is always mindful, and who is moderate in food. He digests his food early, and he lives long". On the other hand, one of the scriptures says that a monk must finish all the food in his bowl so that he may receive water to wash it.

In the more important monasteries, the bell is housed in a special building: a bell tower known as ho rakhang. Although there is no standard design for this structure, most are raised, with the bell hanging in a small space, sufficient for none person to strike it. A steep flight of steps, or a ladder accesses it.

Ceramic Temple fittings

During the Sukhothai period, which probably began in the late 14th century, a series of powerful ceramic figures was produced as architectural fittings for religious buildings. These included the strictly functional, and those which, although practical, were regarded as embellishments. Examples of the first were water pipes for the irrigation system of the city; pillars and balustrades for walls; and tiles for roofs. The latter included windbreak finials for the ends of the ends of gabled roofs, and covers for the projecting ends of purloin. In keeping with their exterior use, the figures were not delicate in manufacture or design, but characterized by a rough strength and energy.

The ruins of only one Sukhothai site retain a few of their ceramic fittings: Wat Mangkon, the Dragon Monastery, which still has parts of a ceramic balustrade, as shown at opposite bottom right. The 'dragon' may well refer to, or have inspired, ceramic guardian figures that are no longer in place. However, despite the very few in situ traces, there are surprisingly large numbers in collections.

Notably, the decorative pieces have little to do with Buddhism, despite their being incorporated on monastery buildings. Common figures are dragons, fierce guardians and praying celestial beings: thewada. The dragons are particularly striking as they bear no resemblance to any of the normal Thai bestiary used in religious art; they are certainly unlike the naga water serpents that feature so prominently on monastery roofs. Sometimes fired in two interlocking part, the dragons may have been a kind of guardian; several were found at four ancient monastery sites, each located at one of the corners of the city of Sukhothai-perhaps an old belief brought down from the north which the migrating Tai settlers. Dragons suggest a Chinese influence, while the monstrous standing guardian figures probably have a Khmer lineage: at Angkor, pairs of statures guard the entrances to temples. The naga finial in the Ramkamhaeng Musuem, Sukhothai, is of Sangkhalok ceramic. Yaksa or demonic ogre; angel gable finial now in the Ramkamhaeng Museum from Wat Pa Ma Muang, Sukhothai; four-faced finial from Wat Phra Pai Luang, Sukhothai; angel gable finial; and yaksa head, National Museum, Bangkok.

Indeed, the very use of ceramics as such architectural elements is ultimately Chinese, and contrasts with the Sinhalese and Indian influences evident in most of Thai architecture. One suggestion is the link was provided by Vietnamese artisans who worked at Sukhothai, rather than by any direct contact with China (for which there are legends but no evidence). Vietnam followed China in ceramic roof decorations as in much else, architecturally.

Whatever the origins, these substantial ceramic pieces are highly distinctive, most of them the most of them the output of kilns at Ban Pa Yang, near Si Satchanalai north of Sukhothai. The dynamic forms were painted in quite energetic lines, with brown and black overgrazed pigment. Later, some kilns at Sukhothai itself began production, and these are unpainted, in pale Grey and creamy white.

Nagas

There is perhaps no mythological creature that puts in so frequent an appearance as the naga, a water serpent with origins lost far back in time, before even the formal religions of Hinduism and Buddhism. Like the chofa, it graces monastery roofs, though in larger numbers. As we have just seen its long, scaly body forms the barge board of several sections of the roof and are, wherever possible, gilded.

Naga means 'serpent' in Sanskrit, and its first documented appearance is in the Hindu cosmological myths. It also appears in Buddhist legend, reminding us how closely these two great religions were linked. Always, the naga had aquatic associations, and there was even a race of part-serpent, part-human nagas who inhabited the watery underworld. The most important legendary nagas had names. Ananta, also known as Sesha, supported the god Vishnu on a bed of its coils as the two floated on the cosmic ocean and the god dreamed the universe into existence. In another myth, the naga Vasuki lent its body to be wrapped around Mount Mandara so that the gods and demons, grasping its head and tail, pulled it back and forth, rotating the mountain and so churning up the ocean from which it rouse to release magically the elixir of life. At Muchalinda, the naga protected the meditating Buddha form a storm by rearing its large cobra like hood overhead like an umbrella.

Its name shortened to nak in Thai, this serpent arrived with the Khmers who, at the height of their empire in the 12th century, controlled the larger part of what is now Thailand. Great stone balustrades, such as those at the Khmer temple. Much later, especially in the north of Thailand, the naga balustrades were copied as the entrances to Buddhist monasteries at Wat Phra Kaeo.

Nagas, such as those illustrated on left at a gable end of Wat Pan Tao in Chiang Mai, or on right, on the roof finial of Wat Sri Khom Kham in Phayao, have a variable number of heads. There may be just one, three, five, even seven, but always an odd number. By and large, the Khamers preferred their nagas with multiple heads, and they used them not just as balustrades but also as acroters on the corners of their redented towers, and as the lower projections of arches, where they were almost always disgorged from the mouths of yet another water creature, the elephant snouted makara.

The Thais preserved all of these architectural roles entrance balustrade, roof finial and arch in their monastic buildings. Only the religion seemed to have changed, though what had actually happened appeared to be that one belief had been brought it to help another. In Naga: Cultural Origins in Siam and the West Pacific (1988), architect and writer Sumet Jumsai argues that the naga is made so much of because it symbolizes the pervasive aquatic rites and culture of the Thai people. Though not everyone would agree with this contention that Thailand is a "Water based civilization", Jumsai convincingly demonstrates how deeply such water symbols as the naga have permeated ritual and design.

He relates a rural measurement of the amount of water needed for the cultivation in any given year that is known as 'naga giving water' (nak hai nam). Nagas use up water, and the more of them that are around, the drier the year. When water is abundant, only one naga is present, but in as severe drought there can be as many as seven. The monsoon, irrigation, flooding, and the watery network formed by the lower Chao Phraya River and Bangkok's canals (most now sadly filled in for motor traffic) all demonstrate an aquatic legacy, of which the naga is an appropriate symbol.

Eave brackets

The curved and flaring roof-line, so typical of traditional Thai buildings, servers two practical functions that are quite necessary in this tropical country: its height helps dissipate heat through convection; its shape copes well with heavy monsoon rains. The pitch begins very steeply close to the ridge, then becomes more shallow lower down to sluice the water out and away from the building you have to experience a full tropical downpour to appreciate how well this design works. Not only does the roof itself curve gently, but there are usually also tow or three distinct sections, each at a different pitch.

The lower roof projects some distance from the walls: this not only deposits the rain away from the foundations, but it also shelters anyone walking around the building. There are two possible structural solutions for these overhanging roofs. One is to build a surround of pillars, effectively creating a gallery on all four sides. This was a feature of large buildings in the Ayutthaya period, and later in the reign of King Rama III, such as in the Grand Palace in Bangkok.

This is, however, a costly and space-filling answer, and necessary only in substantial structures. For a more modestly sized building, a neater solution is bracket attached to the wall; this is what you can see on almost all monastery buildings. Traditional Thai houses from the Central Plains tend to use a plain bracket, often a pole sloping outwards from the balcony to the eave, but in religious architecture, the eave bracket has been transformed into a symbolic form in its own right, and a focus of artistic expression.

This focus is responsible for interest in the eave bracket, for otherwise, according to Thai architectural historian, Professor Anuvit Charernsupkul, it "would hardly seem to be an architectural component that warranted serious study". Looking at the typical monastery building as a sculptural form, which its intricate decorative order encourages, we can see the carved eave brackets helping the overall form. They give clues to the scale, and in their repetition they link the diagonals of the roof to the vertical plane of the wall. The role they play lies somewhere between an independent piece of wood-carving art and an architect's structural device, and in some cases they have evolved to be primarily secretive, whit the horizontal beam above doing the real work.

The most common motifs are the kanok vegetal design and the large family of floral shapes, and the naga that we have just seen gracing roofs and entrances. However, it is the great variety and idiosyncrasy that gives cave brackets their appeal, as seen here from this selection of the monkey god Hanuman and the sacred goose. Kanok hua nok, at first sight appears to be an intricate floral design but in fact contains the profile of a bird in a kind of illusion which rhymes nicely and means 'vine shaped as a bird's head'.

As well as the variety of individual expression, there are some distinct regional differences. Around the town of Petchburi, south of Bangkok, there developed a particular school of carving, which in the design of eave brackets produced the Praying Mantis style. In the North there is a variation known as Elephant's Ear, a triangular board that fits flush into the corner angle of the underside of the roof beam.

In the Nan valley in the easternmost part of northern Thailand, immigrants, known as Tai Lue, from southern china influence much of the art and architecture. Their contribution to the eave bracket is a varied and fanciful bestiary, all polychromes-often-featuring different animals and scenes on each bracket around a building.

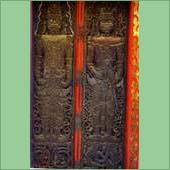

Carved door panels

Thai religious buildings are sited on an axis, and both the viharn and the ubosot almost always face east, thus the long axis of the building runs east-west. In these symmetrical halls, the Buddha images are at the western end of the axial line, facing east through the doorway that is centrally located in the east façade. All of this gives a particular importance to the entrance, which quite often has a projecting portico, and so to the door itself, which can be treated as an architectural component. In keeping with the principle of symmetry, the door has tow panels, and over the centuries these panels have become the focus of artistic expression. After all, the doors mark the transition between the secular world and the sacred.

The first point to not is that in many cases the doorway itself tapers slightly toward the top in a batter. This derives from a general characteristic of Thai architecture of t he Central Plains, including that of houses, in which all four sides of buildings are intentionally inclined for stability.

With the exception of a few magnificent mother-of-pearl inlay doors and gold-leaf stenciling found in some monasteries in the North, the usual decorative technique is high relief carving in wood. Natural weathering gives them a limited life span, even when the natural is the dense, termite-resistant teak of the North, but a few examples from earlier periods remain. One of the oldest is a long single leaf from a door at Wat Viham Thong, Ayutthaya. Despite its weathered condition, it is a very fine example of the best of Ayutthayan art, probably from the first half of the 16th century. A central vine stem runs up the center, in high relief, and from this emerge, at regular intervals, small divinities. On either side, foliage loops and curves down.

Broadly, there are two styles of carved monastic door. One features a guardian on each leaf, usually taking up most of the space. Most of the guardian figures derive from Buddhist and Hindu mythology (here, as in a number of instances, the iconography of the tow religions converges), and some of them may have been inherited stylistically form the Khmer, who occupied Sukhothai among other places until the middle of the 13th century. Thewada, or minor deities, armed with swords, were popular representations. Another was the fierce yaksa, a demonic ogre whose terrible aspect suited it to protective door duty. The rather bizarre figures on the doors of Wat Phaya Phu's viharn in the northern town of Nan are the work of local craftsmen and are known as yama tut. They illustrate well the diversity of carving introduced not only by regional and cultural differences but also by individual skills and ideas.

The second type of door panel carving uses the many varieties of vegetative design worked into patterns-looping vine tendrils known as kan khot, thicker-stemmed vine motifs called khrue that, and several types of flower head that forms the basis of so much Thai decoration. The top panel from Wat Pa Phra Men with the development of individual thewada figures ascending at the center. A variation on this type has a mountain landscape at its base, representing the Himavamsa Forest of Buddhist mythology, and often features a royal breed of lion, the rajasingh.

Door and window pediments

In the North, which in the main developed separately from the rest of the country until the close of the 19th century, monastery doors were further elaborated by what was called a sum: as carved pediment fixed directly over the entrance, right against the façade. Because of the abundance of teak in the northern forests, wood in Chiang Mai and the surrounding valley s was very much the dominant medium of construction. The North also produced large numbers of wood carvers. One can see in these pediments, which serve no structural purpose at all, an unrestrained display of skill.

Both pediment features are famous examples from Wat Phan Tao in Chiang Mai. Employing both high and low relief carving and embedded colored glass, a specialty of the area, the iconography is as complex as it is interesting. Over the main door, the triangular pediment is arranged around a stylized, full-bodied peacock, standing proudly, perhaps even aggressively. On either side, nagas with rearing head cascade down supported at the bottom by kneeling monkeys, while sacred Brahminy geese face inwards from the sides. A tiered prasat, or tower, form the apex.

A curious feature of the pediment is the figure of a crouching dog straddled by the peacock. The explanation for this probably lies in the unusual origin of the building, which was the throne hall, or ho kham, of the fifth ruler of Chiang Mai,Chao Mahotra Prathet. The dog, which appears in the window pediment, was probably the zodiacal animal of the ruler's birth year (the Chinese twelve-year cycle's with each year represented by a different animal was observed particularly in the North). The hall was dismantled in a later reign, rebuilt and consecrated as a viharn.

The even more elaborate sum graces the scripture library at Wat Phra Singh, just a short walk from Wat Phan Tao. It is the finest example of a second type of pediment: attached to the front of the portico rather than to the gable over the actual door. Designed as a multi-tiered prasat with diminishing levers, instead of nagas undulating down the sides, there is pair of dragons with feet, suggesting Chinese influence.

The doors beneath such ornate pediments tended to be treated more simply than the intricately carved panels and typically are decorated with gold leaf designs applied by stencil. It seems that the emphasis has been shifted upwards, away from the doors. The origins of these pediments lie far back in Indian temples, even though the designs have evolved considerably. One of the clearest signs of this is the frequent use of undulating nagas to form the outer frame, with serpents rearing their heads on either side at the lower corners. In many cases, a pair of jaw just behind the neck of the serpent indicates a second creature, a makara, which is actually spewing out the naga. This identical treatment can be seen in India, in stone, in such places as the temples at Khajuraho, the Raths at Mamallapuram, and others. There it was the decoration of a functional element the structural arch and it probably came to Thailand with the Khamer, who made great use of it an Angkor and elsewhere.

Carved Lanna lintels

Much of domestic life in Thailand takes place at least partly outdoors, as befits the climate. Of the tree divisions of the living area of a house, all of them raised on pillars above ground level, only one is an interior space. The terrace, open to the sky, is a working area and, in a large house, a walkway between different buildings. Raised about a foot above this is a covered veranda known as a toen, where most visitors are received, where meals are taken, and where the family generally relaxes. This veranda projects from the interior room, which traditionally is private.

In a Lanna house, the doorway leading from the veranda to the inner room carries above it a decorative lintel, cared in wood and charged with symbolism. Called the ham yon, it is designed to protect the family from harm from both humans and evil spirits. More specifically, it protects the virility of the male householder and the fertility of the female. Ham is an old Lanna term for testicles, and you come from the Sanskrit yantra, meaning a magical diagram, thus 'magic testicles'. The testicles refer to those of the water buffalo, the animal closely tied to the fortunes and lives of farmers. This is one indirect piece of evidence supporting the theory that the kalae represent the buffalo's horn'. The examples here are fairly typical and have ornate floral and vegetal patterns that hardly depict testicles. The strongest allusion on the visible level must be the design of two symmetrical. Roughly circular, whorl-like patterns.

There is a deeper symbolism, however. For example, as the ham yon protects the individual householder, its size is physically related to him. Its length must be three times or four times the length of his foot. Because it must also fit exactly over the doorway, the width of the ham yon is also determined by the owner's feet. There is an added depth to this, for in a Buddhist culture that deems the head the most respected part of the body and the feet the least, any visitor entering the room is, in a sense, debasing himself or herself by passing under the feet of the householder.

The carving and installation of the lintel is one of the rituals of house building or rather was, as the practice is now largely abandoned. In the case of a change in owner ship, the old lintel is assumed to have accumulated power, but that means power for the previous owner. The new owner, therefore, must destroy this by violently beating the old lintel clearly a symbolic form of emasculation and then erecting a new lintel for himself and his family.

khmer statue:thai handicraft:asian handicraft:Handicraft thailand:buddha antique:bronze buddha